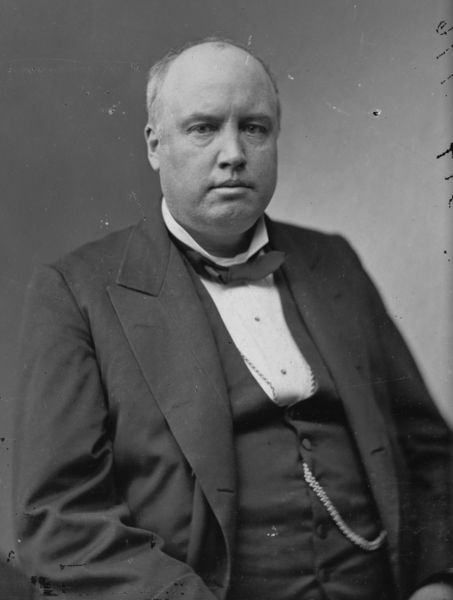

Robert G. Ingersoll

Over the years, even centuries, since the Revolution America has produced some remarkable unbelievers; but the greatest of them all was undoubtedly ROBERT G. INGERSOLL (1833-1899).

His indelible imprint set a hard task for religious apologists. Never before had the Scriptures been so minutely analysed and put to the test of logic, common sense and fair play – and always in the most superb language.

Beautifully worded and perfectly timed sentences which bear comparison to the works of Shakespeare, Ingersoll was born on 11th August 1833 at Dresden in New York state. He was the son of a Presbyterian-cum-Congregationalist minister. In late life this parent was to greatly modify his attitude to religion. His mother died before he reached 3 years of age. Greatly daring for a woman of that time, she had in 1835 circulated a petition for the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia.

He lost his first job teaching in a Baptist academy when he ventured the answered opinion that “baptism with soap was a good thing”. He then became a lawyer’s clerk and studied law. On 20th December 1854 he was admitted to the Bar and in partnership with brother Ebon opened an office in Peoria, Illinois in 1857. The partnership lasted 20 years.

On 13th February he married Eva Parker, ‘a woman without superstition’. There were two daughters to the marriage, Eva and Maud.

From February 22nd to December 18th 1862 he was Colonel of the Eleventh Illinois Cavalry regiment. Posted to Pittsburgh Landing in Tennessee his unit became part of the Army of General Lew Wallace (later author of ‘Ben Hur’).

Early in April he was in the very critical battle Shiloh, the “biggest” battle on the North American continent up to that time. His regiment was highly regarded by General Wallace for mopping up guerrilla bands and won special praise from General Grant’s headquarters for the pursuit of Confederacy troops from Corinth, Tennessee in October.

On 16th December he was ordered 50 miles to Lexington to deal with a raiding party. With 2 field guns, 200 of his own men and met on the way by 500 from other units, he ran up against General Forrest with 2500 men. On 18th December after hand to hand fighting near the field guns his force was overwhelmed and the remnants of the 11th Cavalry taken prisoner of war.

In later years he was to become strongly opposed to killing and to ministers, especia1ly Southern clergy who notoriously misrepresented the action at Lexington.

Eventually returning to his 1egal practice he also began reading widely of all the great writers, philosophers, historians, scientists and poets from the classical days of antiquity through to his own times. An exceptionally fast reader, he also had a photographic memory and could recite 30 poems straight off from a poet he had read only once.

In the mid 1860’s he wrote to brother Ebon, a Congressman in Washington, about the width and depth of his reading. He compared three heathens Zeno, Epicurus and Socrates who had never heard of Jehovah or the Old Testament with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob and concluded that the standards of the Heathen were superior to the Patriarchs.

His legal ability was becoming recognised and from 1867 to 1869 he was Attorney General of the state of Illinois. From 1869 he took 6 years off from active participation in politics. That was the year which marked the real beginning of his great series of anti-religious lectures. Although later legal success would have made him famous on its own it was the lectures which first brought coast to coast recognition as a nationally known figure.

These lectures with titles like “Some Mistakes of Moses”, “The Gods” (1872 in which he paraphrased Pope ‘An honest God is the noblest work of man’), “About the Holy Bible”, “The Ghosts”, “How to Reform Mankind” , “The Liberty of Man Woman and Child”, “Orthodoxy”, “Superstition”, “Progress”, “Some Reasons Why”, “The Foundations of Faith”, “Heretics and Heresies”, “What Must we do to be Saved?”, “Myth and Miracle”, “A Lay Sermon”, “The Christian Religion”, “Humboldt”, “Rome or Reason”, “The Truth”, “Is Divorce Wrong?”, “My Reviewers Reviewed”, “The Devil”, etc. eventually reached about 40 different lectures. The last, “What is Religion?” was delivered in Boston on 2nd June 1899. Each lecture ran to more than 20,000 words and kept him speaking for two hours. Instantly successful the lectures filled halls and auditoriums and took him to every State in the Union except North Carolina and Mississippi.

Leading newspapers recognised him as the greatest orator of the era. His choice of words, and confidential style of delivery made each person feel they were being spoken to personally. People like Mark Twain, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Walter Whitman, Henry Ward Beecher (an admirer during political campaigns) Eugene Debs and Clarence Darrow all tried to muster the best of their word language to describe the sublime qualities of his oratory. Leading newspaper editors who came to hear him personally marvelled at how large audiences would listen to him for three hours without moving. Audiences ranged from a thousand to five thousand people. Sometimes he lectured every night for a full month then a week’s rest before lecturing for another thirty nights in a row. Over the years he lectured in just about every town of any size in the whole U.S.A.

On 13th April 1878 lectures up to that date were published in printed form so that there could be no misrepresentation about what he had actually said. All lectures were eventually published. Ingersoll was always a strong supporter of women’s rights. In the days long before radio or T.V. his magnificently eloquent oratory brought wide publicity and the attention of scores of newspaper reporters – even a publication “64 Interviews with the Press”.

Naturally there were clashes with leading clergy of the day, especially a noted Brooklyn evangelist Rev. Thomas de Witt Talmage, D.D. who preached and had published a series of six sermons. Ingersoll replied in kind, by dealing with each point raised in the same way he dealt with religious problems in his lectures. There were also about a dozen other clergymen of sufficient, note for Ingersoll to reply to by way of printed publication.

For years newspapers had a field day with a great variety of cartoons, including one of a tug-of-war showing Talmage, Manning and supporters against the Devil, plus Ingersoll and supporters with the Bible as marker and the protagonists equally matched, although the knot appears a fraction in favour of the Devil’s team.

Through the columns of the ‘North American Review’ during the 1800’s the religious controversy spilled out beyond American shores. First there was Dr. Henry Field D.D., then Judge Jeremiah Black, followed by William Gladstone (Prime Minister of Great Britain) and Cardinal Manning. It was an intellectual debate on an elevated plane and produced literature with a high degree of merit. During the prolonged exchange of ideas Ingersoll won telling points against all his adversaries who, one by one, retired from the debate.

On the political front he gave dozens of speeches in favour of Grant, Hayes, Garfield, Harrison and McKinley, the assemblages sometimes reaching thirty thousand people. Garfield called him “Royal Bob” and wrote saying “Your path has been one broad band of blazing light”. “The Plumed Knight” speech of 1876 brought widespread fame. Many contemporaries believed he could have been President if he had abandoned his unbelief.

Ingersoll’s wit was phenomenal. Very early on the lecture circuit a minister asked him to name just one thing where he could improve on the Creation of the Lord. “Well”, he replied, “for a start I’d make good health catching instead of bad.”

Although lectures took up a few months of most years he maintained his extensive legal practice throughout – Peoria, Illinois to 1877, Washington to 1885 and finally New York until 1899.

Winning the Munn Whisky Trial in 1876 brought much publicity but it was the Star Route Case (1881-83) which elevated him to the topmost pinnacle of legal fame. Conspiracy to defraud 5 million dollars in relation to mail contracts was alleged against ex-Senator Stephen Dorsey, his brother and another. Considered a near impossible case, Ingersoll won brilliantly by pioneering a technique and style which was to become standard courtroom practice in later years. It cost the Government one million two hundred thousand dollars to prosecute the case – a lot of money in 1883.

For many years Ingersoll’s income was believed to exceed $100,000 a year but he lived well, gave a lot of money away and was involved in several unsuccessful mining ventures. His widow left $183,000 when she died in 1923.

He continued all his pursuits up until his death from angina on 21st July 1899. Cremated in New York, his ashes were kept by his wife in an elaborate urn until her own death, then by daughter Maude until 1932 when the ashes of both were interred in Arlington Cemetery. The tombstone bears the inscription “Nothing is grander than to break chains from the bodies of men – nothing nobler than to destroy the phantoms of the soul”. There is also a large bronze statue of him in Glen Oak Park, Peoria.

On August 11th-13th Ingersoll admirers held a Festival (Sesquicentennial) in Peoria and laid a wreath at the statue. T.V. and Press attended.

By Iain MacKinnon